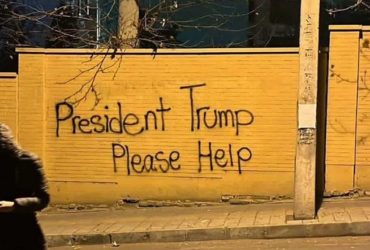

Photo courtesy of the U.S. Embassy in Venezuela.

Venezuela owes American oil companies an estimated $10–12 billion in international arbitration awards stemming from Hugo Chávez’s 2007 nationalization of the country’s oil industry. That year, Chávez ordered foreign firms to convert their holdings into joint ventures in which the state-owned oil company PDVSA would hold at least a 60 percent stake or leave the country altogether.

Several U.S. companies, including ConocoPhillips, refused to surrender majority control and had their assets expropriated by PDVSA, including major projects at Corocoro, Hamaca, and Petrozuata. Venezuela failed to pay market-rate compensation and, in many cases, did not negotiate in good faith. Arbitration panels later found that the seizures constituted unlawful expropriations or violations of Venezuela’s treaty obligations.

As a result, the companies filed claims with the World Bank’s International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes, which arbitrates disputes between foreign investors and sovereign governments. In 2019, ICSID ruled in favor of ConocoPhillips, awarding $8.7 billion in damages for the seizure of its three oil projects. Venezuela sought annulment of the award but failed in January 2025, when ICSID upheld the ruling. With accrued interest, approximately $8.37 billion remains owed.

ExxonMobil was awarded $1.6 billion in 2014 for the expropriation of its Cerro Negro project, followed by an additional $77 million award in 2023. U.S. courts enforced the ExxonMobil judgment in September 2025.

U.S. courts have repeatedly ruled that Venezuela’s state oil company is legally indistinguishable from the regime itself. In the Crystallex case, a U.S. District Court in Delaware determined that PDVSA functions as the alter ego of the Venezuelan government, making its U.S.-based assets, including CITGO, subject to seizure to satisfy creditor claims.

A U.S. Court of Appeals later upheld a 2018 ruling permitting the seizure of CITGO to enforce a $1.4 billion arbitration award. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit separately confirmed Venezuela’s liability for the 2010 expropriation of U.S. company assets.

Beyond arbitration enforcement, Venezuela also faces extensive exposure under U.S. contract law. Most Venezuelan sovereign and PDVSA bonds are governed by New York law and are subject to the jurisdiction of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, which imposes a six-year statute of limitations on claims.

As bondholders and arbitration creditors pursue recovery, senior U.S. officials have openly characterized the nationalizations as theft. Vice President Vance stated that Venezuela’s stolen oil must be returned, while President Trump described the seizures as one of the largest thefts of American property in U.S. history.

Following the removal of Maduro on January 3, 2026, President Trump signed Executive Order 14373 on January 9, declaring a national emergency to safeguard Venezuelan oil revenues. The order exempts funds held in U.S. Treasury Foreign Government Deposit Funds from judicial proceedings, blocking creditor seizures and placing oil revenues under U.S. control. It authorizes the Department of Energy to sell seized or turned-over Venezuelan crude, with initial targets of 30–50 million barrels, while Treasury maintains sanctions but issues licenses allowing exports to the U.S. Gulf Coast to ensure proceeds bypass sanctioned individuals.

Trump stated that Venezuela would turn over up to 50 million barrels of oil to the United States as partial repayment. The first sale, valued at approximately $500 million, was completed in mid-January 2026. Reports indicate that proceeds were routed into offshore accounts, including at least one in Qatar, rather than being held solely in U.S. Treasury accounts. Venezuela reportedly received about $300 million through local banks, while the bulk of the funds remains under U.S. control.

The administration argues that routing Venezuelan oil revenues into offshore accounts protects the funds from creditor seizures while allowing the executive branch to control allocation for debt repayment, infrastructure reconstruction, and humanitarian aid. Qatar has emerged as a key location for these accounts due to its role as a neutral financial hub with strong U.S. ties and its ability to facilitate transactions outside direct U.S. jurisdiction.

Critics argue that the structure is unconstitutional, citing Article I, Section 9 of the Constitution, which grants Congress control over spending, and warning that offshore accounts lack the transparency required when U.S. resources are involved. To date, however, no court has ruled on the legality of the arrangement.

The executive order invokes national-security authorities under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, asserting that the funds serve public sovereign purposes. Supporters counter that the approach mirrors past U.S. handling of frozen assets from Iraq and Afghanistan, where presidents exercised broad discretion over foreign assets as part of foreign-policy and national-security decision-making.

The administration is pressuring U.S. oil companies to reinvest in Venezuela as a condition for recovering arbitration and bond claims, effectively prioritizing U.S. creditors in any restructuring. President Trump has argued that Venezuelan oil production could be restored within 18 months with U.S. support, calling on companies to invest an estimated $100–180 billion of their own capital to rebuild infrastructure, modernize extraction, and raise output from roughly 800,000 barrels per day to historical levels exceeding 3 million barrels per day.

ExxonMobil and ConocoPhillips are in discussions but have signaled they will not commit new capital without restitution for past losses. Halliburton and SLB are expected to supply equipment for refinery rehabilitation.

Despite these efforts, major firms remain cautious, with Exxon describing Venezuela as effectively uninvestable due to political instability and low oil prices. Caracas has introduced a new oil bill offering improved contract terms to attract foreign investors, though it stops short of fully enabling the administration’s plan. The proposed model shifts toward Production Sharing Agreements, allowing U.S. companies to recover costs and profits through a share of output while Venezuela retains sovereignty and receives royalties, taxes, and revenue shares. Proceeds from oil sales are held in U.S.-controlled accounts, with distributions expected to prioritize repayment to U.S. creditors, infrastructure rebuilding in Venezuela, and returns for participating companies.

For the United States, offshore accounts allow the administration to prioritize repayment to American creditors while potentially expanding global oil supply. Increased Venezuelan production would give U.S. companies access to the world’s largest proven oil reserves, boost American energy firms, and could lower global oil prices and U.S. gasoline costs. The strategy would enable repayment of billions owed to U.S. investors, generate jobs across the U.S. energy sector, and reduce Chinese and Russian influence in Latin America.

For Venezuela, the funds are intended to support economic recovery, with the first $300 million already disbursed for local needs. U.S. investment could revive a collapsed oil industry, generate employment, restore fiscal revenues, and address humanitarian shortfalls. Proponents argue that post-Maduro political stability, combined with debt restructuring and U.S. oversight, could attract additional foreign capital, stabilize the bolívar, modernize refineries and the electricity grid, and raise living standards while limiting corruption that plagued prior regimes.

The post How Trump Plans to Recover Billions Venezuela Owes the US appeared first on The Gateway Pundit.