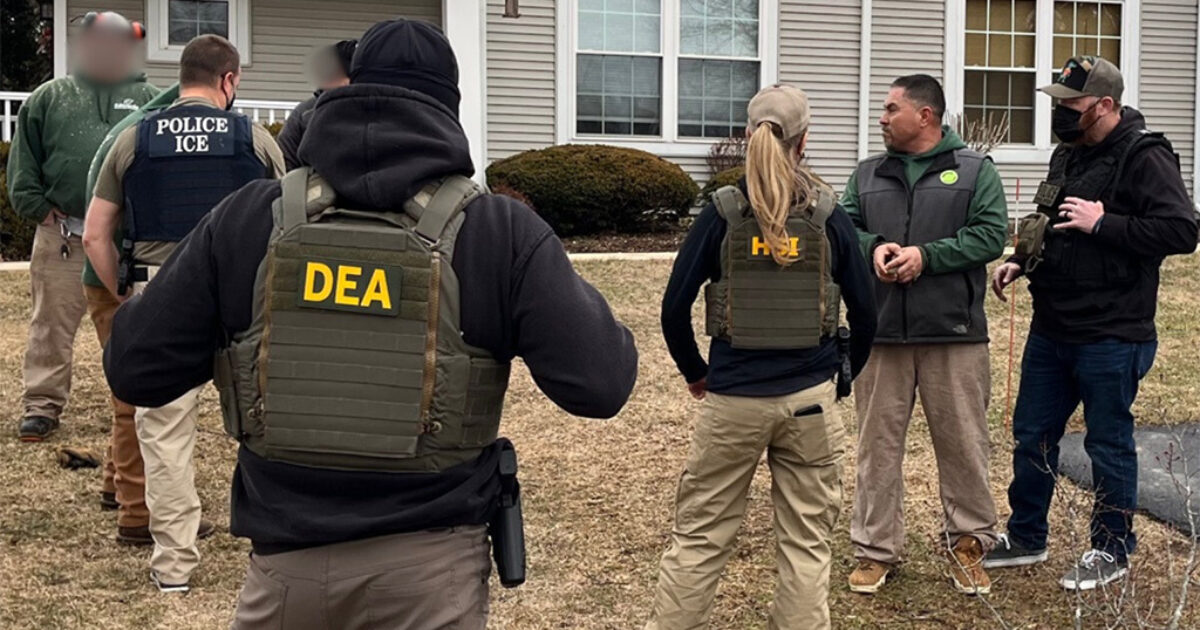

Photo courtesy of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents have been authorized to forcibly enter homes without a judge’s warrant under a May 2025 ICE memo obtained by the Associated Press. The memo permits entry based on administrative warrants issued by immigration officials rather than judges. Critics argue this conflicts with Fourth Amendment protections and overturns guidance given to immigrant communities for decades.

The memo directs ICE officers to use Form I-205 (Warrant of Removal/Deportation) to forcibly enter private residences to arrest individuals with final removal orders. Officers must knock, identify themselves, state their purpose, and give occupants a reasonable opportunity to comply voluntarily. Entries are limited to between 6 a.m. and 10 p.m., and officers are instructed to use only necessary and reasonable force if entry is refused.

The memo relies on a legal determination by the Department of Homeland Security’s Office of General Counsel, which concluded that nothing in the Constitution, the Immigration and Nationality Act, or federal regulations explicitly prohibits the use of administrative warrants for residential entry in these circumstances.

This reverses prior DHS guidance, including a 2021 ICE document stating that administrative warrants do not authorize forced home entry without consent or exigent circumstances.

The administration argues its interpretation is legally sound because judicial review already occurred during removal proceedings. ICE and DHS maintain that administrative warrants provide sufficient probable cause for arrest since targeted individuals have already received due process leading to final removal orders. They argue DHS previously interpreted the Fourth Amendment too restrictively.

The administration contends the Fourth Amendment does not bar this practice in the immigration context, citing Supreme Court precedent and congressional recognition of administrative warrants for certain enforcement actions. Although no statutes changed, the administration’s legal interpretation shifted from viewing administrative warrants as insufficient for forced entry to sufficient when executing final removal orders.

A change in interpretation does not make it unconstitutional. The Supreme Court has overturned its own constitutional precedents 145 times since 1789, demonstrating that constitutional interpretation can change without altering the Constitution itself.

Courts regularly reconsider how constitutional provisions apply. In immigration enforcement, the Supreme Court in Afroyim v. Rusk (1967) reversed Perez v. Brownell (1958), altering its interpretation of when American citizenship could be revoked. The Constitution did not change between those rulings, but the Court’s understanding of it did.

This interpretation has drawn criticism for potentially violating the Fourth Amendment, which historically requires warrants issued by neutral magistrates for home entries absent emergencies. Legal critics argue the policy conflates administrative warrants, which lack independent judicial approval, with search warrants, contradicting longstanding precedent emphasizing the sanctity of the home.

Courts have recognized limited exceptions to the Fourth Amendment warrant requirement in immigration contexts. In INS v. Delgado (1984), the Supreme Court allowed immigration officers to enter factory buildings with a warrant or employer consent, treating workplaces as public spaces. Courts have also upheld warrantless enforcement in exigent circumstances such as immediate threats to safety, imminent destruction of evidence, or hot pursuit.

In United States v. Martinez-Fuerte (1976), the Supreme Court upheld brief questioning at fixed immigration checkpoints without individualized suspicion. However, lower courts have consistently ruled that ICE violates the Fourth Amendment when agents forcibly enter homes without a judicial warrant and without recognized exceptions. A 2024 federal court ruling in California banned ICE from using similar tactics, deeming them unconstitutional.

Critics warn of risks including erroneous raids on U.S. citizens’ homes, traumatic encounters, and escalations leading to violence. However, these concerns exist with immigration enforcement generally, regardless of warrant type. Whether ICE uses administrative warrants or obtains judicial warrants, both rely on the same ICE databases and records.

A judge reviewing a warrant application would have no independent way to verify citizenship status or investigate the accuracy of ICE’s evidence, and as long as ICE presents sufficient evidence to meet the probable cause standard, the judge would issue the warrant. This is essentially the same determination ICE makes when issuing an administrative warrant.

The distinction critics emphasize is not about the accuracy of information, but about the constitutional principle of having a neutral third-party review evidence before authorizing home entry. The theory is that judicial oversight provides an independent check on executive power, with judges potentially questioning whether the evidence is sufficient, requiring additional documentation, or refusing to issue warrants that seem questionable. Critics also point to documented incidents of wrong-address raids and citizen detentions that have occurred even under judicial oversight in other law enforcement contexts.

The administration’s position that administrative warrants tied to final removal orders constitute a sufficient exception has not yet been tested or upheld by the Supreme Court. The fact that prior administrations interpreted the same constitutional language differently does not establish that the current interpretation is unconstitutional. Courts will ultimately determine which interpretation prevails based on constitutional text, precedent, and legal reasoning.

The post New Warrantless Home Entry ICE Policy Sets Up Constitutional Showdown appeared first on The Gateway Pundit.