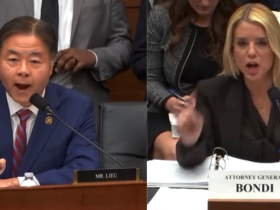

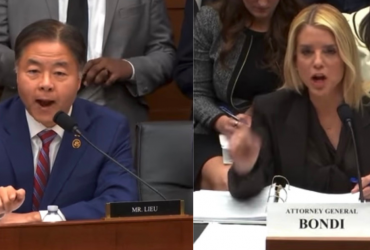

20-year-old Sarah Beckstrom, an Army Specialist, and 24-year-old Andrew Wolfe, an Air Force Staff Sergeant, were shot by Afghan terrorist on November 26, 2025 – via CNN

Guest post by Dan Kiger

The following are my personal views based on professional and personal experience. They do not represent or reflect the official views of the U.S. government or my previous employers.

As West Virginia National Guard member Sarah Beckstrom (20 years old) is laid to rest and Andrew Wolfe (24 years old) fights for his life after an unmistakable terror attack, let’s remember a few things:

They both have families and fellow soldiers who are struggling as you read this.

Let’s give thanks to Sarah and Andrew, who represent a population of young people who continually volunteer to serve us and swear a sacred oath to protect America from all enemies, foreign and domestic.

Sadly, this terrorist attack was not a surprise.

Now for the brutal truth: This catastrophe was guaranteed to happen. How do I know this? Throughout 2021, I sat in a command watch center (think 24/7 nerve center for a military command). My job was to track and relay every significant report coming up from units in the field and back down. That winter and spring, the entire U.S. military was still tangled up in COVID mitigation and vaccine rollouts while trying to keep global readiness on life support.

On April 14, 2021, President Biden announced that all U.S. forces would leave Afghanistan by September 11, 2021.

Our looming departure from Afghanistan was not just another “ongoing operation”—it was the most significant and consequential military drawdown in recent history. From where I sat, it was painfully obvious that the highest senior political leaders were not treating the Afghanistan departure like the complex, life-and-death event it was. It was background noise until it suddenly wasn’t.

Only 17 days after President Biden’s announcement, the Taliban launched their final country-wide offensive on May 1, 2021.

From early spring on, anyone reading the daily intelligence reporting knew exactly what was coming. Province after province and district after district fell throughout the spring and summer—Badakhshan (on China’s border), Kunduz (on Tajikistan’s border), Faryab (on Turkmenistan’s border), and dozens more.

Taxpayer-funded trucks, Humvees, helicopters, weapons, and ammunition were handed to the Taliban on a silver platter almost daily. Key gateways to Kabul, like Maidan Shar, fell quietly. The writing wasn’t just on the wall; it was spray-painted in 10-foot neon letters on every Hesco barrier at least five months before the Taliban captured Kabul.

Retired General Kenneth F. McKenzie, then-Commander of CENTCOM, stated during his 2024 congressional testimony before the House Foreign Affairs Committee: “The events of mid and late August 2021 were the direct result of delaying the initiation of the NEO for several months, until we were in extremis and the Taliban had overrun the country.”

A NEO (pronounced “nee-oh”) is a Non-combatant Evacuation Operation, which is a military mission that evacuates U.S. civilians and other approved non-combatants from dangerous situations overseas.

The President ordered the NEO on August 14, 2021. A day late and a Dinar short. Kabul fell on August 15, 2021.

Everyone (Afghan allies, American troops, contractors, embassy staff, and every coalition partner) knew that falling into Taliban hands meant torture and death, especially for locals who had worked with us since 2001.

When the collapse became inevitable, tens of thousands tried to flee. While I believe most of the withdrawal debacle stemmed from incompetence rather than malice, it seems senior leaders in Washington dismissed those of us who knew the truth on the ground.

As a retired Army official and security expert once told me, “Allowing the Department of State to lead the military evacuation was sheer stupidity.”

Yet, despite U.S. military recommendations to evacuate via a secure airbase we controlled at the time (Bagram, Kandahar, and Jalalabad, plus several others), senior political leadership in Washington made the incomprehensible decision to run the entire NEO through Hamid Karzai International Airport (HKIA) in the middle of Kabul.

Instead of dispersing the exodus across multiple defended airfields, they deliberately funneled every desperate soul into one chaotic, indefensible choke point ringed by Taliban checkpoints—creating the textbook definition of a target-rich environment. Any private fresh out of boot camp could have told you it was suicidal. Our political leaders did it anyway.

Furthermore, it was operationally impossible to properly vet even a small percentage of the thousands who boarded evacuation flights out of HKIA.

Over the 20 years we spent in Afghanistan, we never had anywhere near enough human intelligence, counterintelligence, military police, FBI, or other security personnel on the ground to thoroughly screen Afghan nationals and third-country nationals.

Most intelligence assets were dedicated to finding, fixing, and neutralizing strategic threats or threats against the current government.

Retired General Mark Milley, former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, testified alongside retired General Kenneth McKenzie in 2024 and highlighted how the accelerated retrograde of U.S. forces after President Biden’s April 2021 withdrawal announcement eroded critical enablers, including secure bases.

He stressed that HKIA’s urban, exposed setting rendered it vulnerable to overwhelming crowds and insurgent incursions.

The Abbey Gate bombing, bodies falling from C-17s, parents tossing infants over razor wire, evacuees being hunted and executed—these were not surprises to those of us who knew the enemy.

They were the predictable, preventable result of decisions made months earlier by people who chose symbolism and optics over basic military sense. An ounce of common sense would have prevented multiple tragedies, including the recent terrorist attack in Washington, DC.

I’m not arguing that we should have stayed in Afghanistan indefinitely with the same footprint. No one sane believes that it was sustainable or strategically smart.

But the way we left was tactically brain-dead, strategically catastrophic, and above all morally indefensible. It was negligent, reckless, and completely unnecessary.

We didn’t just withdraw—we handed the Taliban the keys to a fully stocked arsenal worth billions in American weapons, vehicles, aircraft, and equipment.

On top of that, we surrendered control of Afghanistan’s untapped natural resources, including world-class deposits of copper, gold, rare-earth elements, lithium (critical for batteries), uranium, oil, natural gas, iron ore, chromium, gemstones, and more, all estimated at $1–3 trillion.

Who cashes in on this now? The same regime that harbors al-Qaeda and stones women in soccer stadiums. Well done bureaucrats.

The Taliban is a medieval terrorist caliphate, now transformed into one of the best-equipped conventional armies in Asia, flush with cash to fund global jihad and regional chaos across the Middle East and Central Asia for at least the next decade.

And we’re all going to pay the price in blood for years. The attack on Sarah Beckstrom and Andrew Wolfe is only the beginning.

We now know the terrorist who attacked Sarah Beckstrom and Andrew Wolfe had previously worked for and with the U.S. government, assisting with and conducting direct action operations.

Proper vetting to see if someone is suitable to kill, capture, and disrupt insurgents or terrorists in Afghanistan is not—I repeat not—the same type of vetting that’s needed to see if someone is suitable to live and reside in the United States.

As someone who spent time in Afghanistan and Iraq, both in uniform and as a contractor, I can say there were truly courageous, honorable locals who risked their lives and their families’ lives to help us and to try to build a better country. I spent far more time with them than with Americans.

When you live in close quarters, train together, eat the same food, crack jokes, bleed together, and sometimes die together, you form bonds that don’t break.

Americans—whether CIA, DIA, special operations, conventional forces, contractors, or diplomats—naturally want to help the people they come to know and trust across multiple deployments.

But I can also say I never 100% knew any of them (locals we employed) for certain and could not verify much beyond cell-phone affiliations, past reporting, and what others said about them.

To put the vetting nightmare in perspective: no-shit-there-I-was in a bazaar in Wardak Province when a shop owner offered me—for $25–30 cash—a genuine Afghan National ID card (called a tazkira).

That’s right: a standard-issue, white-guy, red-blooded West Virginian like me could literally buy Afghan citizenship on the spot for the price of two Chipotle burritos—or, to readers in W.Va., less than four of Tudor’s Biscuit World’s signature biscuits.

Damn is right! That’s how airtight the “official” identity documents were that we were supposedly using to screen people. “Manana” indeed! (“Thank you” in Pashto)

The biometric system we pinned all our hopes on was essentially flawed from day one. Afghan naming conventions alone broke it: Mohammad, Mohamed, Muhammed, Mahmud, Mohammad (with an extra “m”), etc.—all treated as completely different people by the database.

Add the fact that at least three-quarters of the male population in any province was supposedly born on 1 January (the default date when no one knows the real one) and a positive ID became a coin flip. Worse, the “blacklist” was a joke.

Get banned or flagged at one forward operating base for suspicious activity? No problem—just walk ten miles to the next base, spell your name with one extra letter or drop a letter, and you’re a brand-new hire.

The system saw “Mohammad” and “Mohamad” as unrelated individuals. Most security guards never dug deep enough to cross-check photos or aliases—or didn’t have the capability to do so.

And then throw in local Afghans running some of the initial checkpoints. Another mess for another article.

Some other reality on the ground: in Afghanistan, ordinary life guaranteed some overlap with terrorist networks. Your cousin drives for the Taliban to feed his family.

You pay $20 at a Haqqani checkpoint so your truck doesn’t get torched or commandeered. Your Nokia pings the same cell tower as an IED facilitator.

That doesn’t automatically make you a terrorist—it just makes you Afghan. Our biometric vetting was never designed to distinguish unavoidable everyday contact with insurgents from actual active membership.

The result: we either pretended the system worked (and waved wolves through the gate) or treated every Afghan as a potential threat (and alienated the very people risking their lives to help us). Either way, we lost.

Let’s be honest: we almost never knew, with any certainty, the real identities or affiliations of most locals with whom we worked.

Ask any OIF/OEF veteran how many ways “Mohammad” can be spelled on official documents, or whether we ever truly verified affiliations, date of birth, family tree, or past associations.

We couldn’t. We never had the resources, the access, or the strategic patience to do it right. Don’t believe me? Ask an OEF veteran how many “green-on-blue” incidents (Afghan partners killing coalition forces) they knew of.

Fast-forward to the D.C. terror attack. By now the dots should be visible and easily connected: the predictable consequences of that chaos are still arriving on our shores. Ask the families of Sarah Beckstrom and Andrew Wolfe.

When discussing the D.C. terror attack with the previously mentioned retired Army official, he stated, “Out of the numerous terrorism investigations I’ve seen, it always runs in the family.

An uncle, brother, aunt, cousin; someone is also radicalized and either supporting that organization or a direct-action member.

The way our immigration system works, once someone immigrates and establishes legal resident status, they can sponsor someone else. So who knows how many radicalized individuals sponsored others who were also radicalized?”

Take the galactic stupidity of cramming the entire evacuation through one chaotic airport, then layer on the complete absence of any serious vetting apparatus (in Afghanistan or upon entry into the U.S.).

We’re talking thousands of people—most with no biometric records, no files, no way to verify the names, addresses, affiliations, allegiances, or stories they gave us (aside from U.S.-issued badges, signed memos, emails, and tips from U.S./coalition personnel)—rushed onto planes while we were simultaneously trying (and often failing) to prioritize actual American citizens.

Multiply the identity-verification problem we already couldn’t solve in twenty years of wartime operations by thousands, remove all meaningful screening personnel and facilities, and do it under fire in a collapsing city.

The “so what” is obvious: every hostile group on earth—Taliban, al-Qaeda, ISIS-K, Haqqani Network, Lashkar-e-Taiba, Iran’s Qods Force, you name it—would have been insane not to slip their operatives into that unvetted river of humanity heading straight to the United States and Europe.

We’re not even talking about opportunists and common criminals who abhor Western values. They didn’t miss the opportunity. We’re now living with the consequences.

And here we are. Yesterday’s most-wanted terrorists—the Taliban leadership, men who once topped every coalition high-value target deck—are now addressed as “Your Excellency” in international forums.

They sit in presidential palaces, sign treaties, issue visas, negotiate billion-dollar mineral deals, attend climate summits and UN General Assembly sessions, and are courted as “legitimate” heads of state.

Their past atrocities are quietly filed under “previous administration” while Western diplomats shake the very hands that once ordered suicide bombings, kidnappings, and beheadings. What a world! Mountaineers look out for our own. America should have done the same.

Rest easy, Sarah. Hopefully we’ll change course from here. Montani Semper Liberi!

Let’s stay indivisible—with liberty and justice for all.

Here are three practical, actionable Courses of Action (COAs) for the U.S. government to consider in the wake of this tragedy.

These build directly on the issues highlighted—such as vetting failures, rushed evacuations, and the long-term risks of unverified immigration—and aim to prevent future attacks while honoring the sacrifices of service members like Sarah Beckstrom and Andrew Wolfe.

COA 1: Overhaul Vetting for High-Risk Immigrants

Upgrade biometrics with AI for names, ties, and records; mandate DOD/DHS/FBI cross-checks and 10-year monitoring. Scrutinize family sponsorships. Cut aid/immigration to nations indoctrinating hate—no exceptions. (Show me your schools; I’ll show you your future.)

COA 2: Reform NEO Doctrine

Revise JP 3-68: Ban single-site ops; disperse across secure bases. Shift lead to DOD with intel teams. Annual exercises prioritize defensible sites like Bagram over urban traps.

COA 3: Bolster Counterterrorism & Stability

DHS/FBI task force tracks evacuees with ally intel sharing. Expedite deportations on “clear danger” via analyst, investigator, intelligence-collector-only panels—binding, days-not-years execution. Sanction Taliban minerals; reclaim/destroy U.S. assets to starve jihad funding.

The post A West Virginia Veteran’s Warning: Sarah Beckstrom’s Death was Preventable and Predictable appeared first on The Gateway Pundit.